Using recycled glass fines in construction and product design

Glass fines are the small glass particles (typically between 3 and 8 millimetres in size) that are broken during commingled recycling collection, transportation and processing.

The market for using glass fines in new products is relatively undeveloped, so RMIT University partnered with leading sustainable materials producer Alex Fraser Group, and glass designer Mark Douglass, to examine ways to overcome the barriers of recycling glass fines and provide tangible insights for business and investors on the various uses of this low-cost but high-value material.

The project was supported by Sustainability Victoria through a Research, Development and Demonstration grant and resulted in the Glass fines: Final report (pdf, 9.7mb).

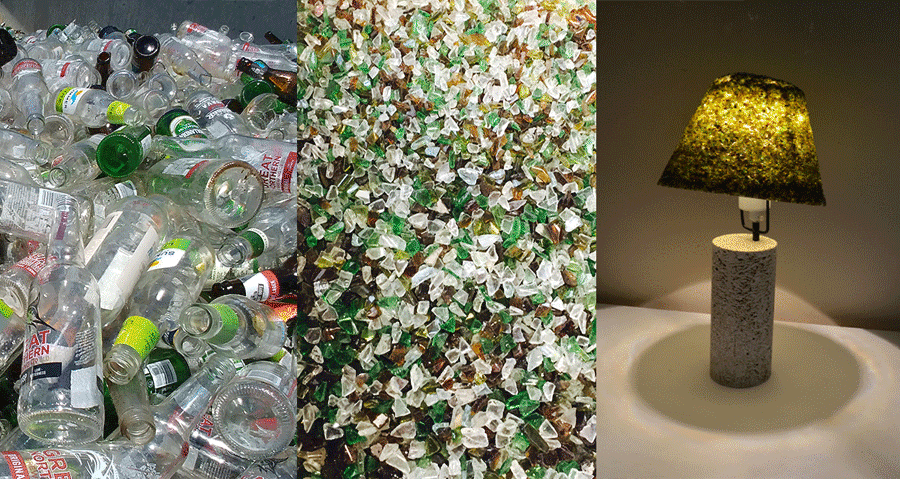

Recycled glass life cycle: Empty bottles > glass fines > new products made from glass fines

Recycled glass life cycle: Empty bottles > glass fines > new products made from glass fines The challenges of using recycled glass fines

Glass fines are considered unsuitable for recycling or remanufacturing into glass for a number of reasons.

- Contamination in recycling bins – Glass fines are difficult to process after they mix with other materials present in commingled recycling bins, including ceramics, stoneware, Pyrex and plastics.

- Difficult to sort at facilities – Glass fines have sharp edges and come in various sizes and colours. These characteristics make the material difficult to sort at material recovery facilities (MRFS), as current machinery is often not built for glass fine specifications.

- Low economic value – Due to the affordability of imported virgin glass, recycled glass fines are a high-supply, low-demand material that give businesses little financial incentive to use recycled glass.

One of the major challenges for refining recovered glass fines is the mixing of colours that occur through the commingled recycling system.

The challenges associated with recycling glass fines often lead to the otherwise valuable glass material being stockpiled or landfilled.

The research project focused on understanding the properties of glass fines and identifying contaminates present from the commingled kerbside recycling process.

Alex Fraser Group provided a range of glass fine samples and a series of technical explorations were undertaken by the RMIT research group to define the characteristics.

The research found that:

- the most common type of glass fine is from soda lime glass, predominantly used in food and beverage packaging

- glass fines are mixed in with ceramics, stones, porcelain, borosilicate and other non-recyclable glass types found in the commingling bin

- contaminants are primarily composed of carbon, sodium, calcium, sulphur, iron, potassium, aluminium and chlorine.

Using glass fines in new products

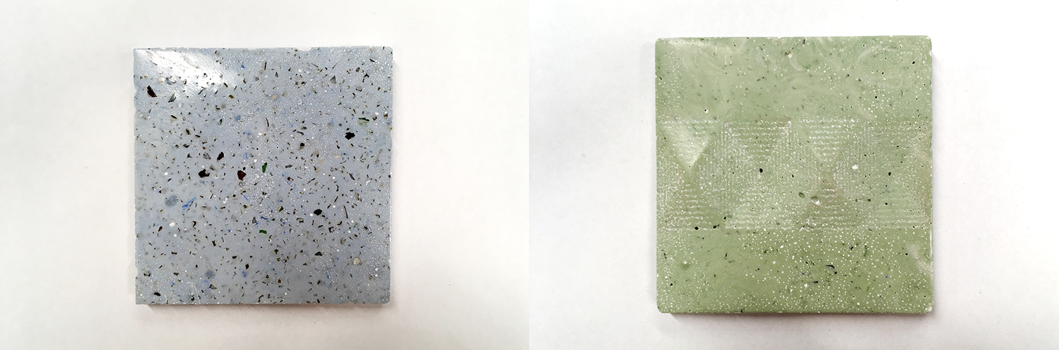

Left image: Polished glass fine cement sample. Right image: Patterned green polished recycled glass fine tile

Left image: Polished glass fine cement sample. Right image: Patterned green polished recycled glass fine tile The research identified and explored a diverse range of new uses for glass fines. These included using glass fines in:

- construction materials and products such as:

- thermal insulation for prefabricated panels

- concrete aggregate

- cement replacement

- cementitious glass

- lightweight bricks

- building products made from glass foam.

- consumer products such as:

- decorative objects (for example, lighting fixtures)

- tiles and bricks

- porcelain and stoneware

- glazes.

And harnessing glass fines for:

- artisanal purposes such as:

- marving (glass blowing)

- fusing

- laminating.

- environmental uses such as:

- water filtration systems

- an alternative to granitic sand and gravels for landscaping

- glass structures that support sea-bed erosion and artificial reef structures

- feed stock for mycelium biocomposites.

This otherwise unutilised material could be used for a range of potential low cost, high-value product development opportunities.

Green and grey coloured recycled glass fine lampshade

Green and grey coloured recycled glass fine lampshade  Rounded decorative containers with a solid recycled glass fine base and curved glass lids

Rounded decorative containers with a solid recycled glass fine base and curved glass lids Sorting and cleaning glass fines

Due to the low financial value of recycled glass fines, the sorting and cleaning methods need to be low-cost and easily integrated into the existing recycling process.

The research group explored a variety of options that can achieve these outcomes.

Sorting techniques

Alternative ways to separate glass fines from contaminants in the recycling process were explored and included:

- Optic identification

This method uses digital imaging and spectroscopy (the use of x-ray fluorescence, infrared, ultraviolet techniques) to separate contaminates (ceramics, stones, porcelain, metals) from glass as well as into colours (amber, green, clear). Typically, optical sorting technology separates glass particles 8mm and above. - Mechanical biological treatment

A low-cost solution for part processing glass fines not suitable for conventional sorting (usually below 8mm). With this treatment, glass fines are processed biologically in digester tanks or piles to separate glass fines from contaminants.

Thermal-based cleaning

Large-scale thermal-based cleaning can be conducted at 550°C for 15 minutes inside a conventional furnace to remove organic contaminants from glass fines.

Chemical cleaning

It is possible to chemically remove the colourants and heavy metals present in glass fines. Colourants are typically metal oxides added in the original manufacturing of glass packaging. Promising methods explored in the report for chemically removing colours include:

- Green chemistry method

Subcritical water is used to purify soda-lime glass. Cations produced from this method can be removed by acid leaching at room temperature. This method produces few or no hazardous by-products. - Liquid phase separation method

Cathode ray tube funnel glass (a popular commercial glass that has often been used in electronics) is particularly high in lead content compared to other glass packaging. Lead can be isolated by a process of liquid phase separation to remove the metal contaminant.

The research group suggests the above methods should be explored further for their feasibility in industrial scale glass fines processing.

Environmental benefits

Recycling glass fines presents the opportunity to tackle a growing waste stream and reduce the need for natural resources.

Diverting waste from landfill

Glass use in food and beverage packaging has increased over recent years. This is likely due to more virgin glass being imported, subsequently entering the waste stream and more glass fines ending up in landfill.

Finding new and appropriate uses for glass fines extends the material’s life cycle.

Reducing reliance on virgin materials and quarries

Recycled glass fines can replace a percentage of materials such as sand and bitumen. By using glass fines in this way, fewer virgin materials are required in manufacturing or construction.

While the product of a recycling and waste commodity industry that is struggling to deal with issues of oversupply and inadequate systems, glass fines offer considerable opportunities.

RMIT’s research report

RMIT University – in partnership with Sustainability Victoria, Alex Fraser Group and Mark Douglass Designs – took a multidisciplinary approach to addressing issues related to recycled glass fines.

The report details challenges associated with recycling glass fines, methods for improving the quality of glass fines and explores a diverse range of innovative applications for the material.

The ideas RMIT reported are designed to demonstrate opportunities for further research and development to develop the market and convert concepts into commercially viable applications.

Download RMIT's Glass Fines: Final report (pdf, 9.7mb).

Projects that have successfully used recycled glass fines

Recycled glass fines, alongside other types of recycled materials, are starting to replace a percentage of virgin materials used in government infrastructure projects.

In 2019, Wyndham City Council increased the uptake of recycled content by trialing a concrete mix design and laying 200 metres of concrete footpath in Geddes Park at Hoppers Crossing, which contained 199,000 recycled glass and plastic bottles.

Downer has partnered with Hume City Council, Close The Loop and RED Group to set a new benchmark in sustainability and innovation, constructing Australia’s first road using a combination of soft plastics and glass.

These projects are examples of the circular economy in action.

Find out more on our Procuring recycled materials for government projects page.